This interview with Lama Ole Nydahl and Caty Hartung took place in Prague, Czech Republic on December 31, 2010.

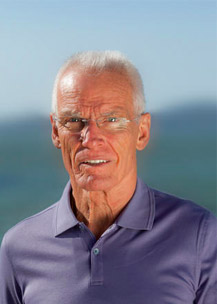

Lama Ole Nydahl

Q: For most people, death is not a very popular topic. Why did you write this book?

Lama Ole: In the world today, Tibetan Buddhism has a lot of unique knowledge in this field. It offers amazing insights into the process of dying and explains what happens afterwards, both during the time when mind digests stored impressions, and then when it incarnates again into a human or some other form in other realms. Even Christianity reckons seven weeks of Lent before Easter, but Diamond Way Buddhism additionally explains the psychological processes that take place here and tells how one can bring beings to the finest possible rebirths.

Q: That is quite advanced knowledge. Is the book written mainly for the general public, for Buddhists, or only for your students?

Lama Ole: Everybody will die someday, so all should be able to use it. Some people will read it mainly for information on how to help family or friends in end-of-life situations. Others will go to one of our Diamond Way centers and get deeper and practical information about our courses in conscious dying (Tib. Phowa). They are offered a dozen times a year in religiously free countries worldwide and thousands have achieved excellent results. Any kind of knowledge, experience or understanding in this area is exceedingly important, for death is a black hole in our collective awareness at the moment. It is something that people either believe and can be influenced, or try not to think about.

Caty: The first half of the book is written in such a way as to help everybody. You do not need to be a Buddhist to derive benefit from it.

Q: Could you tell us about the structure of the book? How is the book organized thematically?

Caty: The whole book has nine chapters. In chapter 1 we explain the contemporary scientific context of death and dying. Chapter 2 focuses on Buddhism in general—teachings on refuge, karma, etc. In the third chapter we describe what one can see when somebody dies and how one can improve the outer conditions surrounding the one who is dying, including which situations people encounter that will help them. In the fourth chapter we actually go into the process of dying. We describe it from the inside, what happens to you as you die. Chapter 5 deals with how you can help the one who is dying and how in this regard to apply the Six Paramitas–the Six Liberating Actions. Next, what is for me the most important chapter: how to use the process of dying and death itself to develop. It was the key reason why we wrote the book and why we structured it the way we did.

This moment is not the worst moment of life. It is a chance, a great opportunity–one that you should prepare for and look forward to. If you are Buddhist, it is your chance to get enlightened. This is the pinnacle of the book: It completely turns the view of the reader upside down and shows him new perspectives.

Q: Can you say more about this chapter?

Caty: It is this turning point that is so special about Lama Ole’s book. Rarely is this optimism so clearly expressed. The whole book has this central theme, namely that the moment of death is in fact a great opportunity for anyone who is able to control one’s mind.

Lama Ole: We were thinking of a subtitle “Using Death as The Way.” The optimism is so powerfully expressed because I experienced it myself in a near-death experience, that the teachings of our high lamas tally completely. Their description of a pure land state is backed up by my own experience.

Caty: Lama Ole is the expert on dying. He teaches Phowa every year to thousands of people. And one applies this method in death.

After the sixth chapter we get to the Bardo teachings. Bardo means a time of transition. It refers to the time between physical death and one’s rebirth. It describes how the process of dying actually is not finished but continues. If you did not yet use your first opportunity while dying, there are possibilities later. We established a timeline showing the appropriate moments where you should apply the Phowa practice.

In the eighth chapter we go into more detail and describe the different forms of Phowa, the possibilities they give us and what to expect during a Phowa course. In the ninth chapter we talk about the teachers Lama Ole has met and how they died. The book ends with the death of the 16th Karmapa.

Q: For those who simply come across the book and know nothing about Buddhism—how should they read this book?

Lama Ole: I think chapter by chapter, taking one’s time. Or by getting a brief overview the first time around and then later becoming more familiar with the material that one is interested in. It is a practical book for learning how to die. It will flourish deep in the mind.

Caty: If someone knows that he or she will die soon, he can read just the fourth chapter. If you know that your mother will die soon, you reread chapter 3 and 5. In such moments you don't need to read all 200 pages. You get a shortcut to the necessary knowledge. We have put the book together specifically for this purpose.

Q: In recent years a couple of Tibetan Lamas have published books on this topic. Also a translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead is available. What is your special contribution to the topic? How does your book differ from the others?

Lama Ole: The first thing to know is that the ordinary Tibetan Book of the Dead is only for people who have received a specific empowerment called Shitro. This is an empowerment on the forty-two peaceful Buddha aspects from our heart and the fifty-eight critical ones from our brain center, which appear when one dies. However, if one does not have this rare empowerment, one will not experience the many forms that are described there. There will instead be gusts of wind, loud sounds or bright lights as one’s emotional and intellectual borders dissolve. People should know that in general they cannot expect to meet images of such forms and may instead experience their subconscious content, through images from their last life.

Caty: I think that the big difference is that you will understand the content. I have read most books on the market that have this theme, and there are so many details that are difficult to understand. We made the subject matter approachable for normal Westerners and Buddhists. Lama Ole succeeds in inspiring the modern mind to use life and death for practice and development.

Q: As far as I know you have used quite a lot of scientific material.

Lama Ole: Yes, Among several doctors daring to go beyond the general materialistic view that the brain creates mind, Pim Van Lommel, a palliative care doctor, wrote Consciousness Beyond Life: The Science of the Near-Death Experience. He, and his findings that awareness can exist without a body, are very important. You can find him on the Internet.

Usual science has long taken it for granted that the brain produces mind, but Van Lommel proves that mind can exist without a functioning brain. He describes many cases in which people were clinically dead and without any brain function. When they were brought back to life again, they described what happened in the room while they were dead–usually “seen” from the ceiling. For this reason they now often place large pictures on top of shelves to see if people remember them. It is important whether they know directly what is there, or if they know only when somebody else in the room also knows it.

Q: Is there a benefit for non-Buddhist readers who read the book but do not follow the idea of life after death? Is there for instance advice on how to deal with the death process even though one does not want to practice Buddhism?

Lama Ole: Yes. Of course, all experience the same process. However, it would be like admiring the menu but not planning to eat.

Caty: I think that knowing the death process will help you when dying. We do not have such knowledge in the Western culture. Nobody describes how the organs dissolve and what you will experience while it happens. Even if you do not believe in rebirth, it will still help you to be more relaxed while dying.

Q: What is the core message? What do you hope that the readers will remember after reading the book?

Lama Ole: That people who have generally lived a good life do not have to be afraid. They can think openly about the process and make it part of their lives. The cultures where death is seen as a natural flow or continuation of life are less neurotic than ours. They don’t have this big question mark at life’s end. They have a holistic feeling about things, like the seasons in nature: We are born, we live, we die, we are reborn. I think that this is very reassuring.

Q: Would you say that getting information about these processes already pacifies the mind and diminishes the fear of death?

Lama Ole: Yes, definitely! Anxiousness about what happens at the end of life is like carrying a constant weight.

Caty: Also, applying the teachings of cause and effect suddenly makes more sense.

Lama Ole: And one becomes very grateful.

Q: This book was a twenty-year project. You have been working on this book since the 1990s. Why did it take so long?

Lama Ole: Oh, the usual: During that time we wrote ten other books and started 600 Diamond Way meditation centers, travelling around the world twice a year (laughs). Also we did not have a publisher at that time. Suddenly we got one who knew how important the topic is.

Caty: We also had not yet had many experiences that we could draw on.

Lama Ole: Much human growth and the latest scientific discoveries would otherwise not have been included in the book.

Caty: The teachings had to get more clarified because it is such a complex matter. If you read the whole book, you will see varying possibilities on how one can interpret the teachings. We needed our own process and experiences in order to be able to explain clearly. Even though Lama Ole is the Western expert, he had to gather, translate and share information in a way that makes the Tibetan sources evident and at the same time is understandable for Western minds. This was the process.

Many conditions came together by which the book could be completed. Lama Ole’s accident, Hannah’s premature death, conversations with Sherab Gyaltsen Rinpoche and Professor Sempa Dorje, etc.

Lama Ole: We have taken on a lot of responsibility with this subject matter. That means that we have to be sure.

Caty: Also it would not have been useful to publish this book right after Sogyal Tulku’s big success. If a book with more concise information and methods arrives ten years later, people are more ready for it. If Lama Ole had published his book one year later, nobody would have read it. I think now is a good time for something new and practical to come out.

Q: Lama Ole, you are a Lama who works with death and dying and the Buddhist methods connected with death. How did it happen that you became involved with this theme? Where and from whom did you learn? What are your sources for the teachings that you are giving?

Lama Ole: Actually it was the wish of our Lama, the unique 16th Karmapa. During early 1971 he gave a major empowerment into an eight-armed green form of the Liberatrice called Dolma Naljorma, the Liberatrice for the Yogis. It was an unusual event and people came from everywhere to participate. Karmapa took the form of a fascinating green sixteen-year-old girl while giving it. Hannah and I were placed right in front and were blown away.

The next morning Karmapa said, “You should learn Phowa from Ayang Tulku, who has a fine transmission-lineage for the practice. He is here for the empowerment and I shall tell him.”

But first we had to go home and earn some money. We reconstructed the furniture of one school for difficult children at night and taught in another school during the day. While I had half an hour without classes and was meditating alone, I thought, “We have the money now. We need a sign of where to go.” In that moment some children walked slowly through the room carrying a large outline of India. There was only one name on it. At the southern tip of the country was a circle with “Bangalore” where the B was written without the stroke as a vertical M–meaning both Bangalore and Mangalore. This was what I was hoping for. There is a road from Bangalore to Mangalore across southern India with a large Tibetan refugee camp nearby, to which we had been invited some days earlier by Ayang Tulku.

The invitation also listed things that India’s socialized economy was not able to produce, and as a final confirmation a description of the secret path we had to take to the camp. The next morning a packet of black pills arrived, sent by Karmapa. These little black pills carry his direct blessing. Thus all the conditions said, “Go.”

We landed in Bombay in early January, took several trains to the south and learned thoroughly and well with Ayang Tulku. I had the sign already in the first session. As soon as I heard the sounds for going up, I was already on my back and out. It was similar to an experience Hannah and I had had with a yogi near Base Camp in the Himalayas and I could hardly believe it could be so quick. Touching the top of my head, I found some blood there but still thought, “This cannot be right. I always made so much trouble. It cannot happen so quickly.” We continued and then Hannah got a beautiful sign.

First we practiced in the refugee camp but the Indians did not want any foreigners there. The Chinese claimed that the refugees were criminals and wanted to send them back to be convicted. This is one reason why they established thirteen Tibetan settlements all the way south at Bylakuppe and also at Mundgod further north, which is an hour or two by bus inland from Bombay. These were two main areas where they placed the second wave of Tibetan refugees, who this time fled the Cultural Revolution in China. If we had stayed there, it would have been too difficult for our friends, because they had enough troubles already.

Therefore we practiced in a damp home in the local village with the auspicious name of Kushinagar–City of Happiness–the very name of the place where Buddha died.

From there we moved up to Mundgod, which is a Northern camp. The camp was totally cordoned off so early in the morning we had to sneak in, passing the still-sleeping police. We stayed there for about one month. Since they had a big epidemic of tuberculosis, it was the place to share what we had learned.

Everywhere Tibetans died from that ugly disease. They came down with their highland lungs, which because of living between four and six kilometres altitude can absorb four out of four molecules of oxygen. At lower altitudes in India they needed only one out of four and thus they never took a full breath. They also had no resistance to the disease and very many of them died. Hannah was improving her Tibetan at that time, so she travelled with Ayang Tulku and they gave the explanations and empowerments. I followed a few days later and pulled them through. They were touching in their thankfulness.

Q: So you were practicing the Phowa for a whole month?

Lama Ole: Yes, every day. Sometimes the Tibetans really shocked me with their confidence. I remember one strong fellow. He had elephantiasis. I said to him, “You go to the hospital.” They had a small Danish-style cooperative hospital there, supported by money from the West.

He flatly refused. “No, I go to learn Phowa. This is my chance and I will die sometime anyway.” I saw him in the hospital after he had gotten the sign. He survived. Then with our rucksacks we walked past the check-point on the way out, and the Indian soldiers nearly wrenched their necks, so as not to see us.

Q: Now you are a holder of this special method called Conscious Dying or Phowa. Could you just briefly say what is it?

Lama Ole: When one is alive it is difficult to leave the body because its sensory impressions hold onto the mind. But if the blessing of the transmission is strong enough and the teacher is convinced of sharing something meaningful and good, nearly all manage to open the central channel through the body. It is very important because, unless our motorcycle happens to run into something at high speed–immediately freeing mind from the energy-lines in the body–mind will exit through one of the physical openings: one of the seven in the head, or, in very difficult cases, through one of two lower ones. (Note that the relaxation at death that we normally speak about, which sometimes brings about an emptying of colon and bladder, is independent of this.)

From what I know of Stalin’s death, he left through one of the lower openings, which is to be expected. When consciousness escapes through one of the biological openings, the dead person takes his impressions and thus his karma with him–all the pleasant experiences but also the heavy baggage.

If, through Phowa, the beyond-personal energy flow in one’s body has been opened, then only the stream of consciousness continues, unencumbered by impressions and completely blissful and aware. One takes nothing along. All karma, all subconscious impressions, all blocks and hindrances stay behind. They remain in the energy channels conditioned through the body and do not influence the release from the body. Limitations gathered through the habitual experience of a conditioned world disappear in the buddhas’ energy fields and, since with that the disturbing feelings disappear, now the job is to tackle stiff ideas from the Pure Lands.

Q: In our modern-day world, is there any preparation necessary in order to attend such a Phowa course?

Lama Ole: The more prepared and more keenly aware one is, the more pleasant and fluent will be the result. We do advise that people do 100,000 mantras of Om ami deva hri as a preparation, thus opening up to the Red Buddha and his state of bliss over their head. It changes the whole feel of the practice. When people have no relation to this Buddha and I do Phowa for them, they usually go into a “closed” lotus flower until they learn abstract thinking. Then it opens up, they see the Buddha, and their real development begins.

Q: If people read this book and they gain confidence even without meeting you, what can happen to them in their last moment if there are no Buddhists around?

Lama Ole: If they want it, they will get help. Wherever one directs one’s mind is where one goes. Mind is unobstructed space and whatever one focuses on will manifest. The book creates a hook for whichever ring one may possess. The ring is one’s openness and the hook is the blessing of the Pure Land, the energy field one contacts and will enter. It is always like that.

Caty: Also the people who are now practicing will practice a bit more because they know it is their chance to be prepared.

Q: You also mentioned near-death experiences. Could you say a little more about that?

Lama Ole: Near-death experiences are occasional reminders that mind is not produced by the brain but rather transformed by it. There is an instance where the information is regrettably lost. A woman skiing in Norway slid into a river and under the ice. If I remember correctly, she remained there for seven or eight hours and when they found her, her body temperature was down to thirteen degrees Celsius. When she had been warmed up again and came back to life, there was so little brain damage that only some of the nerve connections to her ankles had been weakened. Everything else was in perfect condition.

She described her experiences to the doctor, who wrote these down, as a good doctor does. When she later left, however, the doctor thought it was weird stuff and threw the notes away. Thus real first-hand knowledge was lost.

Q: But you yourself had an experience that was very much connected with death.

Lama Ole: As I already mentioned, I had an accident where I almost died. My lungs were collapsed, my hip was broken, and the bones in my right thigh looked like cubist art. I was not exactly in good shape.

At that time, an old friend died. A conscientious objector doing public service backed a Volkswagen transport truck with a long metal rod through my friend’s head as he was walking by. It was a brain death, not a heart death. As lama of the family I was asked what could be done. I knew that the family had talked about organ donations already at breakfast. They had all agreed to it. So I said, “Tell me when they will be harvesting the organs,” and the answer was 6:30 p.m.

Caty: Lama Ole was in intensive care at that time.

Lama Ole: The whole situation was unusual, and sending this friend to the pure land of the Buddha of Limitless Light turned into a colossal experience. I found myself inside a big statue that somehow reminded me of the gigantic Bismarck statue in Hamburg. The walls were a beautiful deep red burgundy colour all the way around, made of red brick. My friend’s mind was like an American oval football under my arm. Flying up, I split the head of the statue and saw light but the opening immediately closed up again. I did this several times and with increasing amazement. This had never happened before. Taking dead people up was always very easy and what was happening here was strange.

I relaxed for an hour to see what would come. Then Hannah and Caty came again and said the time had been changed to eight o’clock. What a relief! If I had taken him out at six o’clock, his organs would have been wasted. At eight o’clock the helicopters came to take the organs to different patients, so now everything was perfect. I joyfully saw the top of the statue open up and on the way I noticed that my red Buddha–Öpagme in Tibetan, Limitless Light in English–was standing instead of sitting. Moving up through his red burgundy space I delivered my friend into Öpagme’s heart center in the middle of his chest.

Then there followed a time that I don’t recall because the bliss was so strong. My next experience was being on Öpagme's right side looking at his profile. He looked a lot like Shamarpa. I thought, “Now I am in the Pure Land so I will look around.”

After I had been everywhere and experienced the most amazing things–just like in life from the viewpoint of wanting to be a protector–then at a certain time I knew I had to go down. Otherwise there would not have been anything for me to return to. The last thing I saw were insects who were eating disease-causing germs. Then I was in my body in the hospital bed again.

Q: Why did you come back? There had to be some special motivation connected with that.

Lama Ole: The thought of staying never came up. I consciously came from this world, I did go to the Pure Land, but had to come back because there was much more to do. It was a clear understanding.

That was my most meaningful experience so far, and every time I spoke about my experience, I would repeat, “You cannot believe the beauty of what is waiting for us.”

The hospital had never had a patient like me and I made the doctors’ work very difficult. Everybody else said, “Oh, this hurts and that hurts,” while I said, “Oh, you are wonderful. You do things so well. You have such excellent working relationships...” I was simply continuing in the Pure Land, which makes a clear picture of sickness impossible.

Q: Why do people have so much anxiety in the face of death if it is so promising?

Lama Ole: It depends. I do not think Stalin found the bodiless state promising. I also do not think that Mao Tse-Tung found it pleasant. I do not believe that Hitler, Khomeini or today’s suicide bombers and those who suppress women enjoy it. Here, one experiences the contents of one’s own mind, the results of one’s motivation and the daily actions that arise from there. When sense impressions no longer distract a person, then joy and pain are immeasurably stronger–and last a lot longer–than anything we know or can imagine here. Every connection to something that goes beyond the personal is here the finest friend; and especially if one has opened the central energy-axes in the body through the Phowa and can leave from the top of one’s head, one goes to bliss without any heavy baggage whatsoever.

Q: What is death from the Buddhist point of view?

Lama Ole: It is transformation. Mind is timeless awareness and energy. But, because of its inability to experience itself as part of a whole, it attaches itself to various conditioned states, generating the six realms by the predominance of pride, jealousy, attachment, confusion, greed or hate. But it can also liberate or even enlighten one, through the noble and precious qualities that are the timeless essence of mind. So in the best case scenario since beginningless time one has moved constantly from one universe or existence into the next. When one’s physical constitution is used up, an intermediate situation appears and within seven weeks the next world of experience matures, with or without a physical body.

Q: This is happening to both Buddhists and non-Buddhists?

Lama Ole: Yes, it happens to every being. The question is whether or not one knows the process and has a convincing refuge and can work with the situation. That is the only thing. Just as everybody has a face whether they look in the mirror or not.

Q: Buddhists are generally not so afraid of death. Why not?

Lama Ole: First, one is simply less afraid of the things that one can understand. It is the unknown that scares people. In Buddhism we have many teachings explaining death. They vary according to what the student is able to comprehend. But it is always clear that mind is indestructible space and that no black hole awaits us. Diamond Way Buddhism explains the whole process of death and rebirth, on both the subconscious and the conscious levels, from the disappearance of one’s sense impressions up to one’s rebirth, when within seven weeks our strongest mental tendency has matured and becomes our next life.

Caty: People today are more afraid of dying. Death is rarely integrated into life. In times past, you died within the family unit or surrounded by friends. Now you usually end up in the hospital. Professionals do all the help and care. Corpses are often driven out of the hospital at night so nobody sees them. People are shy or embarrassed to talk with those who are dying. Dying is becoming more “inhuman,” and real information about the process of dying is lacking. The separation of life from death produces the fear of the unknown in modern societies. This tendency has been developing over centuries. Since the 1960s hospices have been trying a more human approach, aligned with the dying person, and their values, care, compassion, knowledge and help for the situation surrounding the dying are a great opportunity to reverse this dehumanizing process.

Lama Ole: Exactly. The stages and events that Buddhism explains become convincing when one has a chance to take part in them.

Caty: It is astonishing when Tibetans talk about death. The way we behave when people die is very emotional, whereas for Tibetans it is completely different. When Karmapa talks about somebody who has just died, it feels totally natural. There is no pain or grief. For them it is just the next step, there is no end to the cycle of life. Death is a part of it.

Lama Ole: What I usually say when people look at death from the angle of personal loss is: “Do not be unhappy when somebody dies. If they were good they will be a lot happier now than they were in their bodies. And if they were bad at least they have stopped making difficulties and piling up more suffering.” The latter thing is practical after a while but often not the first thing to say.

Q: How can one help somebody who is dying if one is not a Buddhist or one does not have Buddhist methods?

Lama Ole: Caty just whispered in my ear that they should read the book. It is a very good idea. It was fun to write it with wise Caty, and I think that it will be very useful, given our clear style.

Q: A lot of people believe that death is the absolute end. They connect the mind with the brain. They believe that there is nothing after death. What should one tell them?

Lama Ole: Tell them that mind is space and awareness, thus not a thing. Tell them that therefore mind neither came into existence nor can it pass away. Fearlessness emerges from this insight. It leads to self-arisen joy over the richness of life and finally to a meaningful relationship to the environment.

It is compelling when you find a place again, totally unexpectedly–as happened to my wife Hannah and me–where you know that you lived there in the last life and then have it confirmed that one’s own high lama from this life grew up there since 1924.

Q: Can we influence our future lives?

Lama Ole: We do that all the time–our wishes, actions and above all our view determine them.